‘How we see a thing…is very much dependent on where we stand in relationship to it’. (Thiong’o, 1969)

A few years ago, I was waiting at Takoradi in a trotro (a public bus in Ghana); I was waiting because trotros always need to be full of people and cargo before they move anywhere, which can take anywhere from 5 minutes to 5 hours. Various sellers were persuading me to buy the usual assortment of chewing gum, toy cars, pies, boiled eggs, face flannels and mobile top up cards. I was enjoying a chocolate ‘Fan Ice’ when a man with a stick appeared at the door – I immediately assumed he was asking for money, and looked away. He then got onto the bus and slid into the seat next to me; I realised, horrified at the bias of my own perception, that he was a paying customer like me, but was blind and needed support. It is exactly people like me, having poorly formed views and unchecked biases, that makes life difficult for those with disabilities. It is also a telling sign of disability in Ghana that I’d only ever seen a blind person begging at the road side before, and never sitting in the transport alongside me, hence the swift assumption based on faulty inductive reasoning.

One of the aims of this course is to find ways to close the divisions that exist between people through conversation and education – whether that divide exists between people of different places, different religions, different gender or sexuality, or different educational backgrounds. I hope that together we can explore ways to consider how we can collectively play a role in this task. In these conversations, we do not always need find agreement in viewpoints and values, but gain further appreciation of what brought a person to such a view. As Appiah (a Ghanaian born philosopher – I recommend you read his Cosmopolitanism), suggests: ‘conversation doesn’t have to lead to consensus about anything, especially not values; it’s enough that it helps people to get used to one another.’ Perhaps there are some values that we can hope to converge on, but upon others, total agreement seems unlikely.

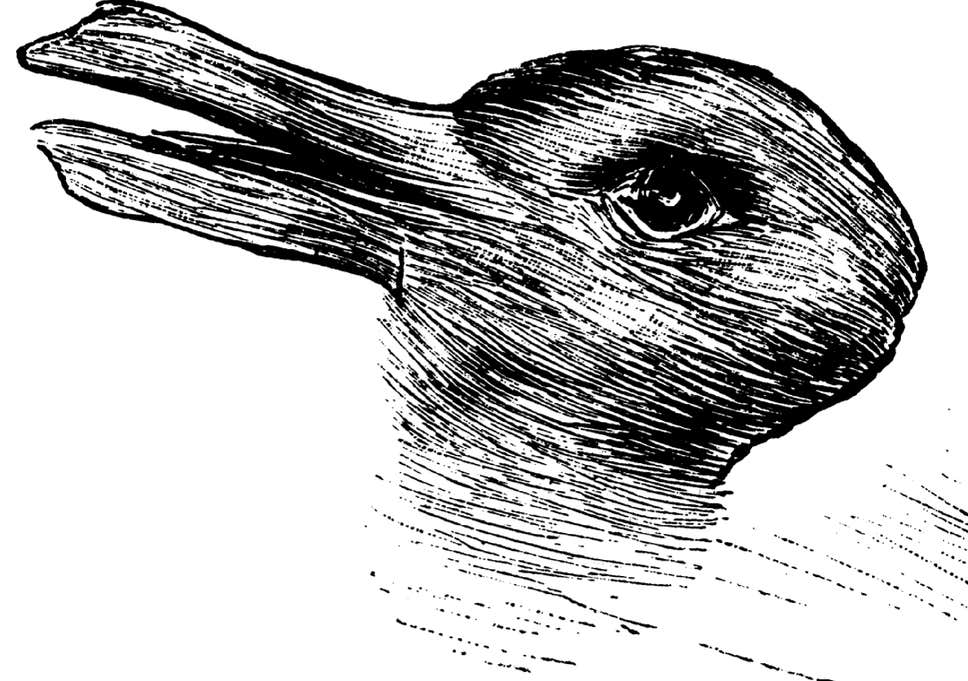

This image is known as the ‘duck rabbit’. Some people will see the duck first, others the rabbit. You may then be able to switch between the two – as Wittgenstein notes in his Philosophical Investigations (an absolute must-read on the philosophy of language), you first see either that it is a duck, or that it is a rabbit. Then when you see the possibility that there are two ways of seeing the image, you see it as a duck or as a rabbit. To me, this image reminds me that the most important starting point for introducing themes in international development, in my mind, is to develop critical self-awareness of how our own perspective, culture and upbringing shapes how we frame the reality we are analysing, considering, crucially, our power relationship with that reality. The duck rabbit also conveys the idea that we are able to see things differently, if we commit to placing ourselves in different metaphorical shoes.

This very famous TED Talk from Adichie (a famous Nigerian author – read Half of a Yellow Sun, a novel set in the Nigerian civil war or Americanah, which partly offers perspectives on identity), perfectly explains ‘The Danger of a Single Story’. I’d really encourage you to find time to watch it all (this is just a short clip), and think of her ideas as an important lens through which to view much of the discussions in this course.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D4pH6TxKzus

Key questions to consider as you watch this:

- In what areas have you been influenced by only hearing a ‘single story’? What ‘single stories’ of poverty have you been influenced by?

- How can we widen people’s perspective and encourage them to consider a perspective that is not usually heard on a topic?

It is clear that widening our perspective and considering the stories of others is central to any exploration of international development. Ian McEwan states powerfully in his book Enduring Love, we live:

‘In the mist of half-shared, unreliable perception, and our sense data has come warped by a prism of desire and belief, which tilted our memories too. We saw and remembered in our own favour, and we persuaded ourselves along the way.’

It is a difficult but important task to be aware of the impact of our own desires upon our judgments with respect to the facts, but I think it is vitally important to try, and to think of ways to change the way in which we persuade ourselves to certain beliefs, when they may lack poor logical foundations, particularly in our current ‘fake news’ political landscape where social media platforms are certainly not epistemologically neutral have been seen as ‘echo chambers’ of our own opinions.

In this exploration of the facts, it is imperative to ensure that we always treat fellow humans as autonomous (self-governing) beings with a voice and mind-set, with interests and abilities often not remarkably distinct to our own. It is useful to remember that there is an asymmetry in our relationship with those with limited access to knowledge of us and our way of life – whilst we may be in the fortunate position of being able to educate ourselves to think about their lives and their development, they may not be with respect to us, or indeed have a sufficient voice in the analysis of their own progression as a country, or as citizens. Should we even be commenting on their development, if they cannot, upon ours? I wonder how many courses exist in Africa, where pupils comment on the best route forward for the development of the UK? How many pupils in India consider how the UK could better tackle issues relating to education, poverty, mental health, and welfare? This recognition of imbalance, and the need for autonomy and constant focus on giving voice to those who have been voiceless is a vital framework for our discussion.

It would also seem odd to consider the lives of the poor in isolation from the lives of the rich, for they are constantly connected. We will consider critically the recommendation of Susan George (1974) that we should:

‘study the rich and powerful, not the poor and powerless…Let the poor study themselves. They already know what is wrong with their lives and if you truly want to help them, the best you can do is to give them a clearer idea of how their oppressors are working now and can be expected to work in the future.’

In Sen’s Freedom as Development, a must-read work which has informed the way in which the international community has formulated concepts of development, we are asked to consider freedom as both ‘the means and the end of development’, suggesting that development should aim to create freedoms for people that should enable them to make their own decisions about their development. We certainly need to be aware (as Said argues in his Orientatalism), of assuming that western societies are developed, rational and superior, with the concept of ‘development’ having some universally agreed end. When considering development in Africa and many other ‘developing’ countries, an awareness of the impact of colonial rule is vital and a reflection on the postcolonial approach will be a central element of this course.

History is, to some extent, an art of threading different perspectives into one coherent narrative on what has occurred; Appiah speaks of human experience as a shattered mirror, where each element reflectsdifferent values and none can claim to be the entire reflection of humanity – a traditional Ghanaian Anansi Tale, Anansi and the Pot of Wisdom , similarly warns us of the error in thinking that one person can be in possession of all the facts. At the end of this tale, Anansi (who thought he held all the facts in his pot of wisdom) realises that his son is able to give him advice about how to carry the pot. His reaction is:

“Anansi angrily threw the pot to the ground, where it smashed into millions of pieces. The wisdom scattered all over the world. People found bits of the wisdom and took them home to their families. That is why no one person has all of the wisdom in the world and why we share wisdom with each other when we exchange ideas.”

I really hope this course can act as a means for exchanging ideas between people in different countries, enriching the inter-cultural learning for all involved and critically evaluating all the actions we take in the name of ‘development’ and ‘charity’ to ensure sustainable and community-led impact.

TASK 1:

1. Watch this advertisement for Innocent Smoothie, a fruit drink product sold across the world and owned 90% by Coco Cola. Innocent Drinks has pledged to give at least 10% of all its profits to charity every year.

Write a post below answering some of the following questions: How is the African continent portrayed in this advert? How is development portrayed? Does it match with your own perception of Africa, and the idea of ‘development’? Are there any assumptions or ‘single stories’? How do you think the advert could be improved or changed? Explain your answers.

2. Comment on at least one other person’s post.

NB Please post using first names only for privacy reasons, and include your country in brackets – e.g. Stephen (Ghana)

Here are a few other additional reading/listening suggestions for those specifically interested in the African context and culture:

African Non-Fiction Book of the Week

African Fiction Book of the Week:

A Perspective on the Colonised Psyche: A Review of ‘Nervous Conditions’ by Tsitsi Dangarembga

African Song of the Week:

Do email me with any suggestions for any element of this course. Or if you’d like to write a review blog for a book yourself, let me know.

Cat Davison and the EduSpots team

Please reference this page if using this article.

>

>