This piece is a (slightly!) abbreviated version of an essay already submitted to UCL. All comments welcome, as we’re always refining our ideas and approach.

Can development and development education goals coexist in the school linking process? An analysis of the approach we hope to take at Reading Spots.

Introduction

The British Council’s ‘Connecting Classrooms’ programme specifically advises that international partnerships are established without an element of charitable giving, stating that ‘charitable donations can jeopardise the equity of the partnership’ (British Council, 2017: 22). The reasons for this are numerous, but centre on the negative impact that fundraising and transferal of funds may have on the learning of pupils on both sides of the partnership. It is difficult to gain a measure of how many international partnerships have been established in the UK, with Doe (2007) calculating as part of an audit on behalf of UNESCO, that roughly 1310 international partnerships exist in the UK, involving 105 countries; there is no evidence to indicate what percentage of these links do involve an element of charitable giving.

It is also a widely-noted concern that in many UK schools, partnerships are led by individuals without significant training; as a consequence, many actions intended as helpful charitable gestures, are in fact causing harm in other countries: for example, Martin (2007: 149) references the negative impact of ‘Operation Christmas Child’ in the Gambia, a predominantly Muslim country, and Burr (2007b) highlights issues centring on ‘Northern’ schools shipping out of date technological ‘cast-offs’ without thinking of the consequences of offering broken computers. Certainly, we are wrong to assume that ‘laudable outcomes will always emerge from the linking process’ (Leonard, 2008:66); as Gorski (2008) asserts: ‘good intentions are not enough’.

The Reading Spots project was created in acknowledgement of the possible tension between learning and charitable giving, in the belief that when carefully managed, financial support for communities in the ‘South’ can coexist alongside learning about global issues. The reasons for this fall in line with the notion of active citizenship (Temple and Laycock, 2008); we believe our project can effectively introduce pupils to notions of social justice, yet also empower them with the notion that they are able to make a change through a charity that focuses on enabling potential through the provision of basic educational resources. As suggested by Scheunpflug in employment of Kant’s philosophy, pupils at Brighton College (BC) will be given the freedom to make their own development decisions, guided by informed teachers, through close mentoring (Scheunpflug, 2008: 18). Ultimately, it is clear that they will be in an environment in later life where they will be faced with decisions in relation to charitable giving, and involvement in our project enables pupils to learn about responsible giving alongside key themes in development education.

We will also ensure that the notion of active citizenship is understood in the context of postcolonialist thinking (e.g. Andreotti, 2011); therefore, I shall refer to the policy I am advocating as ‘critically aware active global citizenship’ (CAAGC). It is evident that without specifically promoting the development of critical awareness, we might have very active citizens, channelling their energies fervently, but without sufficient reflection to produce beneficial action. It is clear that in current mainstream citizenship education, critical thinking skills and action do not play a sufficiently central role in a child’s education (see Banks, 2009: 135).

This essay will explore the Reading Spots approach with respect to both international development and development education, and evaluate how successfully the two agendas can combine through our notion of CAAGC.

Theory of Development in Reading Spots’ Work (see the website for background on the charity)

With respect to the overall aims of our development work (which we expose our pupils to), our project is founded on the key notion that we want to help support communities in their desire to develop in the way in which they want to. The capabilities approach coheres with Singer’s preference utilitarianism in acknowledging that it is vital that people are given freedom of choice in the way in which their country develops (Sen, 1999; Nussbaum, 2011; Singer, 2011). Singer and Sen both base their accounts on the observation that humans hold differing value systems: the capabilities approach is resolutely ‘pluralist about value’ (Nussbaum, 2001: 18). Our libraries are not justified on human capital grounds – on the overall impact they will have to the country’s economic development (e.g. see Mincer 1981), though they may indeed contribute to wider economic prosperity in Ghana.

McEwan (2009:212) rightly highlights the importance of agency within the development process. She suggests the importance of being aware of how development is experienced differently in different regions, arguing that we need to listen to this difference and give ‘voice’ to people living in the South who are usually not heard. We became quickly aware that the voices we listened to were often the local political or educational leaders, and thus spoke to a wider range of people, also ensuring that the libraries are led by Ghanaian communities, who agree to fund the salary of a librarian and the costs of electricity before the project is built. Together we create a partnership agreement where mutual aims are agreed.

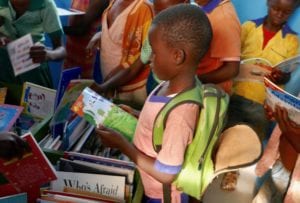

We acknowledge the great need to recognize the postcolonialist position, which requests that we view development work critically in the context of the social and economic legacies of colonial rule, through structures which position previously colonized citizens in the role of the ‘other’. Therefore, we try to ensure that 25% of fiction and non-fiction books within the libraries are directly relevant to the Ghanaian context, and are chosen by local educational leaders rather than by us (see Davison, May 2017b). This is to ensure that Eurocentricism is avoided as far as possible, and that freedoms are maximized, as it is clear that Ghanaian children are more likely to read books that are relevant to their context (see Elbert, Fuegi and Lipeikaite, 2012). If the books are African, they are less likely to be viewed as a ‘gift’ (Stirray and Henkel, 1977), and thus issues with the corresponding power relations and psychological complications are reduced, as this could entrench a ‘recognition of difference’ (Stirray and Henkel, 1977). However, we are wary not to take the postcolonialist lens so far that it becomes demobilizing, in the belief that providing reading resources fundamentally extends capabilities through benefits that arise through the advancement of literacy.

Theory of Development Education

We would describe the relationship that exists between communities in Ghana and Brighton College as that of a ‘link’ that is trying to work towards being a ‘partnership’, moving towards the ‘idealized rationale’ (Leonard, 2008: 67) offered by the Central Bureau (1998) of a partnership that is ‘long-term, fully reciprocal, and embedded in the curriculum’. I would agree with UKOWLA that it is important that not all school links are immediately defined as partnerships (Leonard, 2008:69); crucially a significant voice has to be present in both schools in a partnership such that each member has equal status (Leonard, 2008:70). McEwan highlights the history of a shift between various ‘trusteeships’ in charitable work, and ‘partnerships’ – it can be argued that that mirroring colonial power relations, partnerships often ‘are grounded in foreign (neoliberal) ideologies’ (Power, 2003, referenced in McEwan, 2003:120). Certainly, Reading Spots has to do some work to show that their use of the word partnership is more than ‘fancy window dressing’ (McEwan, 2003).

We seek to combine the intercultural and postcolonial perspectives. Exploring the postcolonial approach, Andreotti (2006b, 2008) warns against reproducing colonial power relations; indeed, we need to recognize the epistemological burdens that may be present within narratives but remain hidden, and recognize that the defects of our own education may damage efforts to become effective development educators (Leonard, 2008: 81). It appears that critical engagement and historical awareness are vital – we thread this into our mentoring in the UK, but could further develop this with Ghanaian pupils with the guidance of their teachers. Andreotti specifically emphasises the need for ‘Critical Literacy’ in education where pupils are given the space to reflect on their own perceptions and those of others, and consider how their own context might have ‘epistemological and ontological assumptions’; this is built upon the key notion that ‘all knowledge is partial and incomplete, constructed in our contexts, cultures and experiences’ (Andreotti, 2006: 7-8).

From an intercultural learning perspective, Fennes and Hapgood (1997:26) agree, stating that ‘only those who know both sides are approaching truth’. This approach suggests that it is not only possible, but important for different cultures to engage in a process of two-way learning. In the context of North South educational partnerships, this would suggest that if carefully managed they could be a vital tool for increasing understanding of those from different cultural backgrounds. Gundara (2000:116) warns against the horrific consequences seen worldwide when ‘mentalities of exclusivity are allowed to breed’ and thus highlights the need for national educational policies which ‘bridge ethnic, religious, linguistic and racial differences’, where education systems give a voice to individuals from marginalised communities, giving them a sense of ‘belongingness’ (Gundara, 2000: 116-121). Crucially, he argues that spaces need to be created in educational systems to enable silenced voices to be heard and empowered in discussion (Gundara, 2000: 123). Teachers play a vital role in establishing this outcome, and must show a willingness to consider the cultural baggage that pupils bring to the classroom, and engage with diversity in pedagogical exercises.

Drawing the two approaches together, through our work, we hope pupils to gain a deep understanding of different cultures, whilst critically analysing their own perspective. In doing so, it appears helpful to think first about ‘commonality and connectedness’ (McEwan, 2009: 213), as a method for avoiding the further entrenchment of stereotypes. Martin advises that we should allow pupils to first focus on similarities due to the greater ‘sense of connection’ that is fostered (Martin, 2007:155), although we are also careful not to solely focus on commonality, due to the fundamental differences in lifestyles, and power (see Gorski, 2008: 523). Our philosophy insists that we try to work actively towards ‘the establishment and maintenance of an equitable and just world’ (Gorski, 2008: 524), investigating the roots of inequality, rather than just addressing the surface-level outcomes and taking what Gorski terms an easier ‘pragmatic’ route, instead opting to move towards a ‘deep shift in consciousness’ through critical engagement in the issues (Gorski, 2008: 517).

Giving a voice to indigenous knowledge and a plurality of voices is vital (Tarozzi and Torres, 2016: xii). It is clear that citizenship education pedagogies need to work hard to combine the shared human experience with an appreciation of diversity. It is certainly important to break down binaries between two worlds where a division is sustained between the ‘active (Northern) agent and passive (Southern recipient)’ (McEwan, 2009: 213). Part of the value of the Reading Spots experience is to remove the notion of Africans as part of the unidentified ‘other’, and rather stand shoulder to shoulder with Ghanaian children as citizens of the world. Further to this, we seek to avoid any focus on Ghanaians as only able to provide the ‘traditional’ form of knowledge, focusing activities on sharing of knowledge on all areas of education.

Combining Development and Development Education Aims: Critically Aware Active Global Citizenship

Offering a clearer idea of how we might achieve, or at least work towards, the challenging development education aims outlined above, through our project we propose a ‘critically aware active global citizenship approach’ (CAAGC). This approach seeks to combine the notion of an active global citizenship journey (Temple and Laycock, 2008), with a postcolonial critique, producing a forward-facing but historically aware approach for learning, which also ensures a level of pupil autonomy. The approach also seems to broadly align with Banks’ ‘transformative citizenship’, in which citizens ‘take action to promote social justice even when their actions violate, challenge or dismantle existing laws, conventions, or structures’ (Banks, 2008: 138). Pupils are shown not only what their rights are, but engage in a process of learning how to exercise them (Tarozzi and Torres, 2016: 20). Androetti similarly identifies two forms of Global Citizenship Education: a ‘soft’ version and a ‘critical’ form. A ‘soft model’ is based on a sense of ‘responsibility for others’ based on common humanity and ethical duty, whereas the critical approach centres on a notion of ‘learning with others’ and complicity in inequality that results from ‘asymmetrical globalisation, unequal power relations, and Northern and Southern elites imposing own assumptions as universal’ (Andreotti, 2006:6-7).

In our understanding of CAAGC, we want to combine notions of a shared humanity, with high levels of critical analysis and social, political and historical awareness, enabling pupils to become what Clark references as a ‘deep citizens’ who are conscious that the identity of others is ‘co-related and-cocreative’ (Clark, 1996: 6). It is clear that without this level of critical analysis of power relations, paternalistic approaches might be unintentionally reproduced (Andreotti and de Sousa, 2012a); we need to ‘challenge global hegemonies’ and not assume that the unequal global distribution of wealth and power is unalterable (Tarozzi and Torres, 2016: 19).

Firstly, we aim to encourage pupils to reflect critically upon the nature of poverty – pupils are moved away moved away from a purely ‘charitable’ mentality towards one exploring social justice, through their own critical analysis (Scheunpflug, 2009: 18). Pupils come to acknowledge that globalization is asymmetrical, both in terms of the benefits gained to each ‘side’ but also in the lack of equivalent ability to be a global citizen through travel (Andreotti, 2008: 56), seen not only in the nature of many one-way travelling partnerships (including our own), but in the asymmetrical attitude towards migration in our world, with differing terms and connotations between ‘ex-pats’ and ‘immigrants’. Pupils consider the idea that Northern ‘partners’ are able to have global powers, whereas Southern partners only exist locally (Dobson 2005:264), and are themselves encouraged to produce solutions to this. It is certainly important to engage pupils in a critical consideration of the political issues underpinning inequality. The most important role of the mentor is to give pupils a complete representation of the facts, and enable them to make a critical judgement upon chains of causality and responsibility. Gorski (2008: 523) suggests that we should be ‘explicitly political’ in our approach; whist I agree that we ought to fight ‘against marginalization and for justice’, due to the requirement for teachers to be politically neutral, I would suggest that claims of ‘systemic oppression’ (Gorski, 2008: 519) need to be carefully analysed and pinpointed rather than assumed. Clear and specific examples of pupils’ complicity in ‘transnational harm’ also need to be given, such as the use of electronic products such as smart phones which use ‘conflict materials’ or illegally mined ores (Bryan and Bracken, 2011: 45).

We encourage pupils to avoid seeing poverty as a physical enemy to be ‘conquered’. To offer a specific pedagogical reference, in Singer’s famous early work which is widely referenced in ethical education, poverty is presented as a condition from which people have to be rescued:

‘If I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of a child would be a very bad thing.’ (Singer, 2016, originally 1972: 6-7)

If the pupils are exposed to this divisive metaphor, pupils should be encouraged to think about why metaphorical swimming pools exist whereby some children are in the pool, and others on the shore? What causes people to be in the pool without the ability to swim? Whilst the metaphor was meant to highlight the irrationality of shifting ethical intuitions between structurally similar dilemmas, the image of the helpless drowning child appears to further entrench ideas of the helpless ‘other’. Furthermore, as Wagner argues, ‘poverty is no pond’ (Wenar, 2011); deciding the right course of action in global challenges, even in disaster relief, is extremely complex (e.g. see Ramacahndran, 2015).

Despite the complexity of action, we should nurture in children a belief that they can make powerful changes in the world. This early form of small-scale action is part of the learning process, and experiencing action in support of a better world through education, whilst considering their impact critically, is to give pupils the tools make positive societal changes. This aligns with Oxfam’s literature, where they suggest a ‘Learn, Think, Act’ approach, which supports our desire to educate pupils in the key issues, encourage them to critically reflect, and to support them in individual or collective action (Oxfam, 2017, online). Similarly, the Development Education Association (2009) aims to get pupils to ‘work towards a more just and sustainable world in which power and resources are more equitably shared’. The notion of their development as a journey in which they move through stages of moving through ‘cognitive, emotional, and moral development in levels of competence’, emphasizes the importance of both the stages of transition, and a particular outcome (Temple and Laycock, 2008: 102).

The desire in children to do something to make a change is to be recognized as something important in itself (Temple and Laycock, 2008: 106). To give an example, two 15-year-old boys came to speak to about their desire to polish old football boots and send them to pupils who did not have any football boots at all. I firstly praised them for their desire to make a change and for coming to see me, before pressing them to think about whether sending old football boots to Ghana was best, or whether new boots could be sent, also considering the football boot trade in Ghana. There needs to be a balance taken in mentoring between allowing pupils to make poorly informed actions, and disheartening pupils (Temple and Laycock, 2008: 106). I started to offer them the structure to shape their own initiative, for they ‘can’t make the journey instantaneously and without support’ (Temple and Laycock, 2008: 106), and also emphasised the extent to which I am constantly reassessing my own beliefs. In this particular instance, the boys shied away from leading their idea – giving evidence to the suggestion that not all pupils will be able to make the ‘full journey’. However, a year later, one boy admitted his nervousness about acting, and applied to be part of the Reading Spots team, speaking passionately about wanting to learn more about global education, indicating that he was now ready to begin what might be described as a ‘journey’ (Temple and Laycock, 2008: 106).

Exploring possible criticisms of this approach, it might be suggested that in our model we are working towards an ‘abstract utopia’ that is ‘so far removed and unreachable that it becomes insignificant for individual development’ (Tarozzi and Torres, 2016: 17-18). However, goals do not need to be achievable in order for them to hold a purpose: the process of progressing towards a hypothetical outcome can be hugely beneficial in itself, both for the development of the individual pupil, and for the society (nationally and globally). It may be, however, wrong assume that our pupils are what Banks would describe as ‘cosmopolitans’, viewing themselves as citizens of the world, with a desire to act in the global, rather than local, interest (Banks, 2009:134). It might be questioned whether their allegiance is indeed ‘to the worldwide community of human beings’ (Nussbaum, 2002: 4), under the recognition that ‘each human being has responsibilities to every other” (Appiah, 2006, p. xvi). Certainly, at the age of 16, it may be unreasonable for pupils to act ‘for humanity’ in such a way; however, it is perfectly possible for individuals to care for the broader well-being of others, to an extent, whilst remaining more specifically attached to ‘their family and community cultures’ (Banks, 2009:134).

It may also be suggested that the very notion of being a ‘global citizen’ is ‘a paradox or simply an oxymoron’ (Davies, 2006) due to the lack of a global state and the differences that exist globally in political systems, ideologies and customs. We may therefore be guilty of taking western values and imposing them normatively on a worldwide scale. However, many would strongly argue that values that centre upon human rights and appreciation of difference, arise from our human nature, and should be globally recognised. Within this, we recognise that injustices are structural embedded, and therefore we are not simply offering a naïve analysis based on an impossible dream (Tarozzi and Torres, 2016: 18). It appears that critical examination of inequality must be embedded in our pedagogical approach in order to ensure that idealistic ideals are not perpetuating Northern superiority. The importance of careful reflection combined with pupil autonomy is not something that the Make Poverty History (MPH) campaign

recognized when they offered a training camp to young activists in the UK. Whilst the broader MPH campaign started with the potential of moving towards a narrative of social justice, Andreotti argues that the focus moved away from engaging the group in critical political discussions about the need for structural change and recognition of individual complicity towards a ‘civilizing mission’ (Andreotti, 2011: 166-167).

Application to Case Study: Brighton College’s link with the Abofour Community

Linking to Oxfam’s notion of ‘Learn, Think, Act’ (Oxfam, 2017), our pupils are offered a basic introduction to development and Ghanaian culture, history and politics, before their trip. During the trip, pupils often come up with a variety of suggestions and questions, such as:

Why don’t we fund a scholarship so that one pupil can return to Brighton College?

Why don’t we pay for their Senior High School education so more of them can go?

Should we give them our spare clothes when we leave?

We carefully talk through all the implications of such suggestions, and without being hit with cynicism, pupils realize that giving is not always a good (asking them to be critical of our own project, too). Through the relationships pupils forge with the Ghanaian children, they quickly further their understanding of their abilities, and their own prejudices. One boy admitted that “it sounds bad, but I had kind of assumed that their mathematical abilities would be worse than ours” (BC pupil, 2016). Instead of judging the pupil, we praised him for his honesty, and together we considered what led him towards this belief in the first instance. Through careful questioning he began to deepen his understanding of the stereotypes perpetuated in the Western media and education system – other pupils and we as teachers also learned much through this process of honest questioning, gaining awareness of our own cultural baggage.

The Ghanaian pupils learn that the ‘white people’ have the desire to contribute to the educational provision in their community. We try to find ways to remove notions of us as ‘saviours’ by explaining that we are simply wealthier than them, offering to them what our school children already have. We thus frame the relationship through a lens of social justice, on the principle that all children have a right to educational resources – if we are able to provide resources, then this is something that we should offer to establish wider equality in educational opportunities. Some complexities arise, however, when Ghanaians want to thank us, in ways that could appear to cement a neo-colonialist relationship. Establishing the balance between diffusing a power imbalance, and accepting their gratitude, can be challenging; however, ultimately, there is a difference in financial wealth between the schools, and to not support them at all with their desire to read books, due to a focus on educational learning, might become an obstacle in itself. The fact that one school is in a position to support the other financially, can feed into the very discussions of social justice that we are encouraging.

Ongoing conversations with our Ghanaian colleagues is the most important aspect of the relationship with respect to creating equity of power and voice. The Director of the school, is often keen to emphasise that this ‘gratitude’ is due to the way in which we act whilst at the school, which has broken down stereotypes of racial superiority in the community. When I specifically questioned him on how the link with us had affected their notion of social justice, he responded:

‘Our concept of social justice is quite simple. Your support and contributions toward the development of the school project shows to them how well you think of them and their future. You and your team have been breaking barriers for social mobility. They learn that all men are equally created and as such should be treated with love, care and respect.’ (Joseph Addae, Wassap, 29th July 2017)

It is clear that our desire to shift the imbalance of educational opportunities due to the equal rights of man to education, is also embedded in their theological foundations. However, Andreotti expresses a clear concern that school links of this kind might always defer pupils back to the default setting of imposing a sweeping narrative over southern partners that they are dependent on our help (Andreotti, 2006: 55); as a response, our pupils will be made aware of the postcolonial framework and will be guided towards a deep reflection on the specific freedoms held by the southern pupils, and the reasons for this. Pupils also quickly realise that the Ghanaian friendships they establish have a considerable impact on their lives, shaping the narrative towards one of equality in respect to the two-way sharing of knowledge. We frequently discuss the power imbalance in play and do not carry out pedagogical activities on the ‘false assumption of an even table’ (Gorski, 2008: 523).

Possible Concerns

There is certainly wide-spread scepticism in the literature about the success of North South educational partnerships that involve charitable giving. Leonard (2008) suggests that charitable links ‘complicate relationships’, going as far as to suggest that such links reproduce a type of ‘charitable colonialism’, questioning whether such financial giving may reproduce a dependency relationship (Leonard, 2008:77). It is evident that the key concern is that it is challenging to create a genuinely equal power relationship; it may be that this is an idealistic notion in itself that is worthwhile as an aim but difficult to create in reality. Visits are often only one-way between schools, entrenching ideas of an asymmetrical globalism. The Marlbourgh Brandt Group have led a link with communities in Gambia for a number of years that did involve two-way pupil trips; however, the travels of Gambian pupils have stopped in recent years due to issues involving visas, and pupils wanting to remain in the UK (Walker, 2015). It is clear that the analysis of the benefits is often swayed towards the schools in the ‘North’ (Burr, 2003, 2006). It is therefore vital that a formative evaluation of projects is taken in which the desired outcomes of both parties are considered.

However, Scoffham (2008) convincingly argues that it is clear that we do not need both partners to offer the same things in the relationship, for their needs are remarkably different. This leads him to conclude that the partnership process ‘doesn’t need to involve equal exchange but can be asymmetrical… It is perfectively valid for both partners to bring different things to the relationship’ (personal communication, quoted in Leonard, 2008: 73). In our relationship established in the Abofour community, we have supported the creation of a small library that is used by the entire community. In return, we have gained much insight about how to effectively run a book club, absorbed inspiring pedagogical techniques, and the pupils all leave acknowledging that the wide variety of knowledge that they have gained from the Ghanaian community, far surpasses anything that they were able to pass on from their interactions with the Ghanaian children and staff. Once again, it is clear that we need to think carefully about the value system that is created to determine the ‘equity’ of a relationship – it appears that transferal of knowledge may be more important to many communities and schools in the ‘North’, than funds.

The critical drawbacks specifically of our concept of CAAGC are certainly present, but can be addressed to an extent by effective mentoring. It might be suggested that pupils lacking sufficient knowledge might act in a way that clashes with development theory, and that teachers who also lack experience and understanding in this field may serve to extend this issue (Temple and Laycock, 2008: 102); however, if we suggested more widely that the possibility of poor coaching could lead to negative consequences, this would lead us to many undesirable conclusions; instead the solution appears to be that teachers running North South partnerships should be given exposure to more CPD opportunities. Certainly ‘global citizenship action without global citizenship values is not our goal’ (Temple and Laycock, 2008: 103) and staff need to establish values before beginning a mentoring program.

It might also be suggested that we are not giving the pupils genuine autonomy in our project (Temple and Laycock, 2008), as they are ultimately encouraged to raise money for a particular library. However, the pupils have to ‘buy in’ to this particular goal in applying to be a Reading Spots ambassador, and we try to give the pupils as much autonomy as possible in determining how their specific project comes to reality, giving them the opportunity to lead discussions with Ghanaians on the design and functioning of the ‘Spot’; in this, there is certainly a careful balance to be struck between steering pupils and directing them.

Conclusions

Goals associated with development and development education can combine through our notion of CAAGC with the outcome of enabling pupils to gain a greater critical understanding of global inequality and realize ways in which they can make a difference. However, for such an approach to be successful, the mentoring of pupils needs to be delivered by experts who are themselves critically aware and constantly engaged in evaluating their approach, thinking carefully about the limitations of our own perspective. Looking forward, we hope to explore further ways in which pupils can become involved in political activism as a response, if this desire arises from their analysis of the causation behind the lack of educational opportunity in remote areas of Ghana. We also hope to provide staff involved in the project to be exposed to core themes of development education studied in this module. There is certainly much work to do in developing pedagogical tools that can address the ‘questions of distribution, knowledge production, representation, power relations, and self-implication’ (Bryan and Bracken, 2011:10).

The main challenge is sustaining a partnership where there is as close to equity of relationship as possible. To achieve this, we need to have further extended discussions with the Ghanaian communities about what they hope to gain from the relationship, and we certainly need to further consider the impact of our financial support of the school’s library upon the development education of the Ghanaian pupils. It is vital to acknowledge (see Scoffham, 2008) that different schools may have different things to offer in a relationship: influence certainly extends far beyond the funds offered, and thus an analysis of ‘equity’ itself is vital – both sides need to have a voice in what is being measured and valued (see Edge, Olatoye, Bourn, and Frayman, 2012)

Cat Davison August 2017